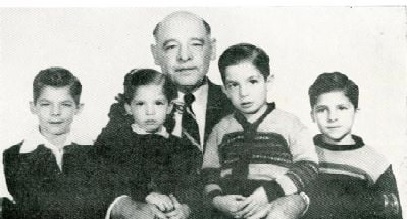

The “vice” President: Abelardo Rodriguez Lujan

It’s said that crime doesn’t pay, but I don’t think anyone says that crime can’t be good investment opportunity. And, while the wages of sin are…well… you know, there’s considerable tax revenue in sin that might be put to good use.

Abelardo Rodriguez Lujan is one of those men who might have led a completely unremarkable life had it not been for the Mexican Revolution. Born in 1889 in Guymas, Sonora there was nothing to indicate a 4th grade dropout, growing up in dusty Nogales, would ever amount to anything. Perhaps it was having his face slashed by two gringo boys on the Arizona side of the border (resulting in a scar he’s have the rest of his life) that turned his thoughts less to revenge, than how to “bleed” the gringos.

A tough little guy, he seemed to be up to anything. A true man of all trades, he was a miner, an ironworker, a would be professional singer, and even for a time a professional baseball player by the time the Revolution came along. Willing to try anything, and not adverse to helping himself when it was to his advantage. Being paymaster for his unit didn’t hurt, though there is no record he was corrupt in that position and he proved to be a better than average soldier, and even better politician.

He had the good fortune when he joined the army to have joined the 2nd Battalion of the Sonoran Constitutional Army (as a lieutenant) and eventually coming to the attention of the Sonoran commander, Alvaro Obregón, the millionaire inventor turned politician turned general… turned politician. Proving his loyalty to the Constitutionalist cause, later fighting Pancho Villa’s rouge units (defeated at the Battle of Celeya), Rodriguez was trusted with military and civil command first in Sonora, and later in Baja California under Obregon and, later, Calles, administration.

In the meantime, somehow (and we probably don’t want to know) Rodriguez had made a tidy fortune given his connections on both sides of the border. It was the Prohibition era in the United States, and as a state governor with control of liquor licenses in border states, it’s easy t guess where at least the source of some of his personal wealth.

it was in Baja though, where Rodriguez’ true shady genius flourished. If the “Roaring 20s” were going to roar, they’d need firewater to keep the roar going… alas, under the 19th Amendment something illegal in the United States. Not in Mexico. Where Governor Rodriguez was quite willing to … er… “assist” US based… uh… “entrepreneurial” importers… and, besides, with Tijuana just a short drive from most of Southern California — with its booming middle-class seeking what was advertised as the “good life” — there was a market for all manner of out-of-sight, out-of-mind extracurricular activities for bored Californians.

This is where Rodriguez becomes such an intriguing figure. While we think of the “self-made man” who rises from poverty and obscurity to wealth and power as likely to forget what it was like, he didn’t. Like the millionaire Obregon, he considered himself a Socialist. And one to do something for the betterment of his people. Certainly he had pocketed his share of “investments” and “assistance to foreign interests”, into a string of more legitimate enterprises, in the fishing and canning industry — in part to prevent foreigners for taking over the business, leaving even more money available for his massive personal contributions to public universities and to pay to build public schools and libraries.

As governor, he imposed both an informal and formal “sin tax”… on prostitution, liquor, gambling (having in the meantime built the biggest casino in North America at a time when Las Vegas was still just a desert jerkwater railway town) and the marijuana and opium trade (yes… he was complicit in that, as well) but the revenues went to a cause only someone forced by circumstances to leave his education in the 4th grade would understand. The Baja would have 100% free public education for 100% of the students.

And, that would be a Socialist education, not the religiously influenced one of the old regime. His strong objection to religious education, and his anti-clericalism — something that appealed especially to Plutaro Elias Calles, Obregon’s successor (Calles’ hatred of alcohol only surpassed by his hatred of the clergy). Coupled with Rodriguez’ loyalty to the regime during an attemped coup (as the richest man in Mexico, the plotters assumed he’d be a natural ally against the leftward trend of the government) brought him into the cabinet.

Obregon … thanks to a constitutional change in the length of the presidential term… was allowed to run again for President. Won.. but was assassinated before taking office. The Constitution had provisions for a president leaving office for some reason (like dying) during their term, but not for a situation quite like this. Calles considered staying on, but Rodriquez and other cabinet officials talked him out of it, settling on following the Constitution had Obregon died after being sworn in. Being inn office (obviously) less than two years, an “interim president” would serve until the next Congressional election in two years. Several possibilities were raised, including Rodriquez, but the logical choice was the Secretary of Gobernation (Interior Minister or Home Secretary), Emilio Portes Gil.

Although a Callas loyalist (and Calles … technically out of office remained, as US Ambassador Josephus Daniels would later call him “the strong man of Mexico”… Portes Gil had his independent streak (he did everything possible to bring an end to the Cristero War and official anticlericalism) … and in the 1929 election, Callas’ man was one he though easier to control… Pascal Ortiz Rubio, then Mexico’s Ambassador to Brazil. It took some hanky-panky at the ballot box (and more than a smidgen of political violence), but Ortiz Rubio easily defeated José Vasconcellos and his anti-corruption ticket.

Ortiz Rubio was not in good health, and an attempted assassination (on inauguration day, when he was shot in the jaw) and — worse for him — was not as much as a yes-man as Calles wanted. Whether it was before or after he read about it in the papers, he announced his resignation — “with my hands clean of either blood or money” — on 2 September 1932. Calles need someone — maybe willing to dirty his hands — to finish out the term.

Rodriguez looked to fit the bill. He wasn’t above dirty politics, but he wasn’t about to just say yes to Calles, either. Rodriquez was devious enough to realize Calles was not a well man, his power was slipping, the country was changing… and Rodriquez already had a fortune estimated at 12 million dollars (about 275 million today) so hardly needed to feather his own next.

Among other things during his short time in office, Rodriguez pushed through the first minimal wage law (before the United Staates, by a couple of months), ruther isolating Calles, publicly humiliating the former president and “strong man of Mexico” openly telling the US Ambassador that he could not consult with Callas, nor was any meeting with Calles “official” in any sense of the word. He eased up on his anti-clericalism, satisfying himself with a public disagreement with the Pope over the meaning of a “socialist education” ehile leaving with restrictions there were on the clergy up to the individual states and not involving the federal government.

In a way… the old baseballer was pitching to his sucessor, Lazaro Cardenas, who was campaining on an openly anti-Calles, pro-Socialist platform.

With Prohibition in the United States having come to an end, Rodriguez would focus his post presidential career to his more legitimate business activities and education. He’d occasionally serve as guest lecturer at the University of California, besides maintaining an interest in the University of Baja California Norte. With hsi US born third wife, he lived on and off in San Diego, traveled the world, and — agains those Mexican rich guys can surprise us — extenively travelling in the Soviet Union, writing perceptive but positive about the Soviet economy.

During the Second World War, he did play a small … but vital — role, serving as Naval comander of the Baja Peninsula (seriously considered in danger of a Japanese invasion and regularly targeted by Japanese submarine warfare) and even as a sort of “offical” dope dealer. The US needed morphine and other opiates, but was cut off from their usual legitimate suppliers, and turned to Rodriquez for help… having him arrange for opium poppy seeds and experts in the field to assist the US in growing their own.

He was a rogue, but no hypocrite, and while he might bemoan his own role in the way the narcotics trade has changed since his death in 1967.. he had nothing to apologize for, something very few of us (and even fewer politicians) can ever say.

Sources:

Samaniego López, Marco Antonio. Breve historia de Baja California. Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. 2022.

El General Don Abelardo Rodríguez Luján. Historia de Hemosillo.net

Estrada Ramírez; Arnolfo. “Abelardo Rodríguez: único político en gobernar a México y dos de sus estados” El Vigia (Ensanada, BC). 27 Feb 2019

Martinez, Rubi. “¿El narco presidente de México?: por qué historiadores consideran así a Abelardo L. Rodríguez” Infobae, 2 september 2023.

Braceros

While campaigning in Iowa last September, former President Donald Trump made a promise to voters if he were elected again: “Following the Eisenhower model, we will carry out the largest domestic deportation operation in American history,” he said. Trump, who made a similar pledge during his first presidential campaign, has recently repeated this promise at rallies across the country.

And, upping the game, US Speaking of the House, Mike Johnson vowed the “round up” 11 million undocmented aliens for deportation.

Both Johnson and Trump point to the 1954 “Operation Wetback” when what was then the Immigration and Naturalization Service attempted to deport 1 million aliens, mostly farmworkers, as their model. The model is flawed, but the whole issue of “illegal” immigrant workers stems from attempts to regularlize foreign workers, going back to the World War II “Bracero” programs… another of those “issues of today” that call for a deeper dive into history.

At the stat of the Second World War, Nazi Germany had bent over backwards to avoid breaking relations with neutral Mexico, hoping to maintain access their mineral and other resources (and provide a “safe space” for espionage against the United States), despite Mexico’s official anti-Fascist policies. However, following U-boat attacks on Mexican flagged ships exporting oil to Allies, on the 28th of May1942… for the first, and only time in its history… Mexico declared war on a foreign country. Or rather several foreign countries, notably Italy and Japan as well.

This presented an open ally to the United States, which was desperately trying to find the manpower for its rapidly increasing military, while at the same time keep its own economy functioning. Mexico was hardly in any position to offer significant military assistance, but it did have one thing the US and allies needed… workers to replace those being rapidly conscripted into the military.

So, under a “memorandum of understanding” between the now allies, Mexico entered into an agreement with the United States that the latter could hire Mexican workers “for the duration” with some stipulations… they had to be paid a mimimal wage (set at 30 cents per hour), provided with sanitation, housing and food, not subject to the US draft, and 10% of their earning were to be withheld until their return home. While mostly meant to replace farm workers in the United States, Mexicans were recruited for other jobs, especially keeping the railroads running.

What constitutes acceptable “sanitation, housing, and food” was, of course, open to interpretation and unfortunately how that was interpreted, let alone enforced, was spotty at best. Worse, although less so for the railroad workers, was that much (perhaps most) of the funds set aside to be paid upon return to Mexico simply disappeared. My sense is that the railroads, being corporate entities with sophisticated accounting practices, were able to track financial expenses, and built in to their costs the future payments. Whereas (and something we forget) is that “big ag” didn’t really exist in the 1940s, and farms were still mostly family owned operations, with varying levels of financial controls. Add too, that many of the farmers were simply unfamiliar with foreigners… perhaps not fully comprehending things like Mexican surnames. That is, José Sanchez García and José García Sanchez might both be employed on the same farm, and as far as whomever was keeping the books, they were the same guy. And, without oversight, of course, some simply took advantage of the situation, paying as little as they could get away with, or their small town banks just dumped everything into some general account and “forgot” about it. Not that there wasn’t corruption on the Mexican side as well.

And, with the end of the war, while the railroad and factory workers were being replaced with “natives”, farm workers — given the massive change in the US economy, with a massive shift to industrial production — farmers needed to replace workers unlikely to ever return to low paid “stoop work”.

IN 1948, given recognition that the booming post-war US economy attracted other Mexicans still willing, if only temporarily, to take on those dirty jobs, with or without official permission… to the detriment of its own farmers and complaints about the conditions under which workers not officially in the program were subjected to, Mexico wanted the program ended, but settled for a compromise in which the US would sanction employers hiring outside the official program, and making the US government, not the individual employer, responsible for the workers. . In 1949 and again in 1951, “adjustments” made, notably holding farmers harmless for allegedly hiring non-citizen workers unknowingly.

Texas having especially become dependent on Mexican labor to keep its agricultural sector functioning was reluctant to enforce even these minimal standards. And, ironically enough, “Operation Wetback” was meant to force Texas farmers to “get with the program” by threatening them with otherwise entirely losing their work force. If that was the plan, it went spectacularly wrong. 100,000 migrant workers and family members (not the million so beloved by politicians bent on repeating the exercise. The million figure includes everyone either denied entry from Mexico, or returned to Mexico in 1954).

Between roadblocks throughout the southwest, raids on social halls like bars and restaurants in rural communities, and pulling workers out of the fields, the deportees were loaded onto buses, driven into Mexico and dumped, sometimes wherever it was a bus driver decided he’d had enough for the day. 88 people died in one event, when the US failed to notify Mexican authorities, or the Cruz Roja, where they had stranded a few hundred people.

Despite the then head of the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service); Joseph Swing’s statement to the public that “The era of the wetback is over”, it became normalized for Mexican workers… with or without official permission, to cross over the border to work. Although there was a drop in Mexican immigration at the time, in 1958, the INS noted that ““should … a restriction be placed on the number of braceros allowed to enter the United States, we can look forward to a large increase in the number of illegal alien entrants into the United States.”. In other words, if there are jobs paying more in the US than a person can find at home, they will come.

The supply of “legal” braceros and demand for employees was always out of balance, but the program limped on until 1964. There was an absurd effort in 1965 to recruit high school and college athletes to work the fields during the summer, which quickly fell apart when the small number of students who participated (only 3000 or the 18,000 recruits ever worked the fields) either went of strike over the poor housing and food issues, or found the work too difficult and quit.

But, then again, by 1965, even with the massive changes in the agriculture as a business, it still came down to people working in the fields for not much money… but more than they could earn in Mexico. Farm workers already established in the United States (mostly of Mexican descent, either those who had the border cross them in the 19th century, or the descendants of earlier migrations, especially during the Revolution) opposed hiring foreign workers at less than they earned.

Still, the booming southwest needed workers of all kinds, and with Mexico largely ignoring the rural communities throughout the 1950s and 60s in favor of urban development, those not migrating from rural Mexico to the cities were moving north looking for jobs that offered a better life than that in the still “backwards” small villages at home.

Farm workers… out of sight for most middle-class Americans, and out of mind were one thing… but the migrants, documented or not, were the kind of people the middle-class saw every day: construction workers, cleaners, delivery drivers, restaurant workers, and so on. Low paid, but very visible people.

And… resented.

No one was sorry to see the Bracero program fade away, although in the aftermath of US and Mexicn bank consolidations in the 1990s and 2000s, the issue of unpaid set-aside wages had still not been settled. Banks, and farms, in the United States had either gone out of business or had been swallowed up by larger banking corporations, and denied any responsiblity. The Mexican banking system had collapsed completely in 1992, and after reorganization, the banks were either sold to foreign corporations or forceably consolidated. At any rate, from both countries, the businesses that should have paid denied any resonsiblity for the missing funds. Eventually, a fund under Mexican government oversight was creted in the early 2000s, but could only pay out to those still having work records from their time in the US.

And now… given the “Bracero” program openly encouraged foreign workers to come to the United States, and that the government in the US turned a blind eye (for the most part) to those workers not officially in the program, but doing the same sort of work, it shouldn’t be surprising that what started as an emergency and temporary solution to an immediate problem (farm workers needing to become soldiers) would become a customary way of dealing with the need for these types of workers when the crisis had passed, but new opportunities had presented themselves. Nor, that as these new opportunities (work in fields other than… well… in the fields) presented itself, that migrants would not avail themselves of it.

Nor that migrants wanted to stay, and did. Nor… given political and cultural developments after the second world war that displaced millions, and required not just a change in occupation, but one in location… and the location offering the best opportunities just happened to lie a bit further north, that the migrant community (legal and otherwise) continued to grow. Especially after 1964 when the United States, which had depended on European immigration discovered its Eurocentric 1924 immigration regulations were no longer serving the country’s needs, and … although they didn’t want to openly say so… they were depending on low wage foreign labor to keep their economy growing.

Are there 11 million “illegals” in the United States? Back in 1954, when the population of the United States was about 160 million, about 9 million were immigrants. The US population is about double what it was then, with about 45 million immigrants. A higher percentage, perhaps (about 10 percent now), but how many have all the right papers, and how to discern that, and how to keep businesses running if 11 million people were to be deported and dumped elsewhere is something hard to imagine. And this site deals in history, not what-ifs.

By the way… given that of all places, Wikipedia had a detailed, scholarly entry on Braceros… warning that it needed rewritten as an encylopedia article, I am posting it almost in its entirity as it stands now before the editors dumb it down.

Cinco de Mayo… conservative nostalgia?

While in the US, today is widely celebrated as some sort of Mexican identity day… and we continunally have to educated the gringos that it is NOT Independence Day, nor even a holiday, there may be a reason it is the informal US “Mexico Day” that might be worth considering,

It was a big deal…. back during Porfirio Diaz’ regime. After all, he made his political career out of his fame as a hero of the war against the French, and was involved in the defense of Puebla. For his coterie, celebrating Mexico’s best known military victory, and Mexican militarism, was a meant to celebrate the Diaz regime itself.

The Revolution, not only ran Porfirio out of the country, but his most ardent supporters among the upper class and old elites as well… most of the latter emigrated to the United States, where — even if in reduced circumstances — would still be the elites within the Mexican diaspora.

While I’ve seen argued (and I lost the source, unfortunately) that the first US Cinco de Mayo celebration was in some Southern California town, simply because the local lemon farmers were mostly descended from those old elites, and it happened that the the 5th of May was during the lemon harvest season, and local agricultural festivals have always been a popular even in small towns. So… based on the Porfirian model of a parade and party… the Americanized Cinco de Mayo.

The modern US Cinco de Mayo is largely a creation of Mexican beer distributors… themselves “elites” in the Mexican American community, or the old conservative elites within Mexico… a faint echo of the Cinco de Mayos of the 1880s.

Another except from Nelly Bly’s 1886 “Six Months in Mexico”:

They flock to the city from mountain, valley, town, and city, clad in holiday attire. Then only one realizes their strength, as they march before the palace where the president is seated on the balcony. The finest looking men in the whole 40,000 are the rurales. They number 6000 and are larger men than Mexicans usually are. These rurales are a band of outlaws who came forward with their chief and aided Diaz during the war. When it was over Diaz recognized their power, and was so afraid of them that he offered them a place in the army, with their chief as general, and they are to-day not only the best paid, but— speaking of their fighting ability— the best men in Mexico. In the first place they are large and powerful and known over the entire country, mountain, town, and valley, as thoroughly as we know our A, B, C. They fear nothing on earth, or out of it, and will fight on the least provocation. They would rather fight than eat, and have a great aversion to exhibiting themselves, as they demonstrated on the 5th of May last, when only 800 could be persuaded to participate.

The good ol’ days?

Nellie Bly in 1885. Must have been stronger in those days:

The soldiers have an herb named marijuana, which they roll into small cigaros and smoke. It produces intoxication which lasts for five days, and for that period they are in paradise. It has no ill after-effects, yet the use is forbidden by law. It is commonly used among prisoners. One cigaro is made, and the prisoners all sitting in a ring partake of it. The smoker takes a draw and blows the smoke into the mouth of the nearest man, he likewise gives it to another, and so on around the circle.One cigaro will intoxicate the whole lot for the length of five days.

Winter of the Patriarch… Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas at 90

Like a Roosevelt or a Kennedy in the United States, being born a Cárdenas almost predestines one to a political career. Son and presumed dauphin to Lazaro Cárdenas …whose presidential term was marked by nationalizing the oil resources, expropriating the haciendas and returning the land to the communes, and lending moral moral (and in the case of Republican Spain, military) support to the anti-Fascists of Europe, … and incidentally born on May Day 1934… it should have been Cuauhtémoc who rose to the presidency to return Mexico to its Revolutionary roots.

Despite Cardenas pere’s post-presidential role as Minister of War during the “War Against Nazifascism” and globetrotting (with Cuauhtemoc in tow) to the post colonial outposts of cold war resistance… meeting and greeting everyone from Chairman Mao to Mexican peasant dissident leaders. However, despite his party having left his brand of revolution aside, settling for the rhetoric of revolution (Lazaro’s “National Revolutionary Party” became the “Institutional Revolutionary Party” — claiming modestly to preserve the “institutions” of the revolution — with a very different structure after he left office in December 1940), Lazaro would stay with the party, even when, at the end of his life (he died in 1970), the mass protests of 1968 exposed huge gulfs between the left and their governors

Not that Cuauhtémoc was entirely silent. At 20, he took a lead in organizing Mexican assistance to the Arbenz administration in Guatemala… the one soon to be undone by United Fruit and the Eisenhower Administration. And, in the early 1960s, joined the MLN,,, a “militant youth” wing of the party,

Although MLN (Movimiento de Liberación Nacional) was a movement within the PRI, it was not limited to PRI loyalists, but sought to recruit Marxists, peasant movements and independents into a viable renewal wing of the party. Even the rich kid, Carlos Salinas de Gotari was a member, although he’d develop a very, very different vision of Mexico than the others, While the MLN was short-lived, dissolving in 1965, several of its more notable leaders would play an important role in the 1968 student uprisings as “elders” (while relatively young, Cuautemoc was pushing 40 by this point) and would be jailed or forced from their jobs. Several would defect to other parties, or other movenets. Still others would find a niche within the party and government bureaucry, seeking change from within. Cuautemoc among the latter.

As a Senator, he supported the election of Lopez Portillo whose administation would come to grief seeking to expand the welfare state on oil revenue, only to face financial disaster as a result. What led to his break with the party was a break in the “Mexican miracle”… and literally shook the country: the 17 September 1986 Mexico City earthquake.

Given the devastation, and the seeming inability of the party to handle the immediate needs of the people, the people responded… not by rioting, or protesting, but by taking control of their needs into their own hands. Everything from emergency kitchens, to security crews, even media coverage was taken on by improptu committees and the small citizens groups and clubs of all kinds..

It was obvious, and not just in the Capital, that the party no longer could, or would, respond to the people’s needs, and while there were those who simply sought to either shitewash the party’s image, or reform, there were enough of those who saw no future for themselves in the party, to consider alternatives.

For the fractious left the magic of the Cárdenas name gave them something to rally around in the 1988 elections… the one he most likely won, but was undone “thanks” to a still not explained computer breakdown followed by an “accidental” fire destroying the computer center. And, Cardenas would run for president twice more (in 1994 and 2000). Although he never won, he did become the first elected “mayor” of what was then the Federal District (today’s State of Mexico City) and the party he would come to lead… the PRD (Democratic Revolutionary Party) would, for a time, control not just Mexico City, but large part of the Mexican south. Although, the PRD would gradually lose its grip and “revolutionary” fervor filling its ranks with time servers and ambitious “grillos” (literally grasshoppers — professional politicians that will jump to whatever party will nominate them for office) and the less committed and has faded into irrelevance (now a junior partner in the conservative PRI/PAN/PRD coaltion, known as PRIAN, to its oppenent, not even rating mention within the enemy ranks.

What makes Cárdenas’ political failure remarkable though is those three presidential elections, including the stolen victory, to today’s replacement. IF AMLO is the “tropical messiah” as he was once labeled, then Cárdenas was his John the Baptist.

Consider what Cárdenas was proposing in his last campaign, as reported by Sergio Munoz in the 28 May 2000 Los Angeles Times:

We have to modify the Constitution to allow for . . . the referendum, the popular initiative, plebiscites. We have to define the tools for impeachment and accountability for public officials. We have to limit the power of the president to make real the balance of powers.

About what that upstart from Tabasco, who like other former PRI activists gave up on reform from within, the “tropical messiah” himself, has been working towards.

Although whatever prescriptions Cárdenas might have proposed in 2000 would probably differ from those offered today, and by the present candidate of the sucessor united left, the same concerns — povery reductions, honest adminstration, power to the people, remain the same. The patriarch can rest easy, in the winter of his content.

- The writer (and scion of European nobility) Elena Pontiatowska was leading a “ladies who lunch” writers’ group: wealthy women with time on their hands, and more importantly, having cars. Women would want to “do something”. And could… running around the city, getting information on what was available or needed where, and chauffering news crews for the media outlets.

- In Tlatelolco, an anonymous Boy Scout put on his uniform and served to coordinate the adult and teenage rescuers digging through collapesed apartment buildings.

- A seamstress’ union led the rescue efforts at a collapsed factory site, a snack vendor at a high school, and so on.

Those who do not learn…

We need the rain, stop squaking

Oacacan Senator Adolfo Gómez Hernándezm who sits on the Agriculture and Rural Development committe, knows we really, really need rain. Something we can’t do anything about, although I suppose we can try.

The Senator is a Mixteco, and his people have an app for that… one that had the Senate clucking. Gómez invited in a clutch of his fellow Mixtecos to hold a ceremony in the Senate outdoor plaza, to placate Tlaloc — the rain god — and offer him a chicken.

Well, in the old days, it was a baby, but apparently, there being some sort of Senate rule against bringing livestock into the complex (everyone remembers when farmers rode into the Chamber of Deputies on horseback a couple years ago) and his Morena party leaders … apparently unwilling to upset their Green allies, or maybe the vegan voters … had egg on their faces making a stink over the whole thing.

I’d post the video, but the Senate communications office took it down… they chickened out.

And we’re still waiting for rain.

OOPS!

Sorry about the double posting (with slight variations) today… I’m still screwing up some wordpress functions and had some “issues” with the computer last night when copying and pasting.

Nabokov and Mexico? Maybe…

Today is the 126th anniversary of Vladimir Nabokov’s birth. His best know, and most notorious, novel being Lolita, a repost from June 2013:

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins: A Mexican?

22 June 2013

tags: Horny middle-aged men

Thanks to Sterling Bennett for this:

Charlie Chaplin married his second wife, actress Lita Grey (real name Lillita Louise MacMurray), in Empalme, Sonora on 26 November 1924 in the offices of Registrar Civil Ignacio Haro. Judge Haro provided three witnesses, Carlos Álvarez, G. Félix and Isidro de Jesús Guerrero, while Chaplin brought along three witnesses of his own, , Charles T. Reissner (who understood Spanish well enough to translate for Chaplin), Edward Manson and Louise S. Curry. Also attending was the bride’s mother, Mexican-born Lilian Spicer. Lilian, something of a classic stage-mother, had pushed the Hollywood born and bred Lillita into the film industry, where she had been working with Chaplin when the girl was 12.

At the time, Empale was both a company town, serving employees of the U.S. owned Compañía del Ferrocarril Sudpacífico, and wealthy Californians seeking a refuge both from prohibition and those pesky State morals laws. Three months pregnant with the future Charles Chaplin Jr. Lita was 16. The groom was 35, and — under California law — liable to be imprisoned for sexual relations with a female under 18 who was not his wife.

To no surprise, the marriage lasted less than two years and became notable mostly because Lillita, aka Lita, received what was at the time the largest divorce settlement in U.S. history (600,000 for Lillita, and a 100,000 trust fund for Charles Chaplin Jr and his brother Sydney, born a year after Charles).

Sue Lyon, the ultimate screen Lolita, 1962… obviously not Mexican

According to Chaplin biographer Joyce Milton, Russian emigre Vladimar Nabokov, transformed the California Mexican Lillita into the New England college town Lolita, being much more interested in the story of a middle-aged European seduced by a young American… or, in this case, Mexican-American.

Saúl Santana Bracamontes, Charles Chaplin; la boda en Empalme (El Tribuna [Cd. Obegón, Sonora] 24 November 2012), Wikipedia, IMDB.

Today is Nabokov’s 126th birthday. In honor of one of the best American writers in Russian (or, Russian writers in American, or just plain writers ever) … a repost from 2013:

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins: A Mexican?

22 June 2013

tags: Horny middle-aged men

Thanks to Sterling Bennett for this:

Charlie Chaplin married his second wife, actress Lita Grey (real name Lillita Louise MacMurray), in Empalme, Sonora on 26 November 1924 in the offices of Registrar Civil Ignacio Haro. Judge Haro provided three witnesses, Carlos Álvarez, G. Félix and Isidro de Jesús Guerrero, while Chaplin brought along three witnesses of his own, , Charles T. Reissner (who understood Spanish well enough to translate for Chaplin), Edward Manson and Louise S. Curry. Also attending was the bride’s mother, Mexican-born Lilian Spicer. Lilian, something of a classic stage-mother, had pushed the Hollywood born and bred Lillita into the film industry, where she had been working with Chaplin when the girl was 12.

At the time, Empale was both a company town, serving employees of the U.S. owned Compañía del Ferrocarril Sudpacífico, and wealthy Californians seeking a refuge both from prohibition and those pesky State morals laws. Three months pregnant with the future Charles Chaplin Jr. Lita was 16. The groom was 35, and — under California law — liable to be imprisoned for sexual relations with a female under 18 who was not his wife.

To no surprise, the marriage lasted less than two years and became notable mostly because Lillita, aka Lita, received what was at the time the largest divorce settlement in U.S. history (600,000 for Lillita, and a 100,000 trust fund for Charles Chaplin Jr and his brother Sydney, born a year after Charles).

Sue Lyon, the ultimate screen Lolita, 1962… obviously not Mexican

According to Chaplin biographer Joyce Milton, Russian emigre Vladimar Nabokov, transformed the California Mexican Lillita into the New England college town Lolita, being much more interested in the story of a middle-aged European seduced by a young American… or, in this case, Mexican-American.

Saúl Santana Bracamontes, Charles Chaplin; la boda en Empalme (El Tribuna [Cd. Obegón, Sonora] 24 November 2012), Wikipedia, IMDB

On the substack site, of late:

The “youth vote”: Rebels with a cause

The floundering Gálvez campaign: Dead woman walking?

The Embassy siege and the election: The debate eclipsed by the Embassy siege

The long and winding road… Alan Seeger and family

What unites investment publications, Electric cars, the French Foreign Legion, a Communist, T.S. Eliot, and the American Legion? A dive down rabbit-hole of a Mexican footnote.

While only slightly surreal, considering it’s Mexico City, that bastion of US conservativism … the local American Legion post… not only for a period hosted poetry readings … but was named NOT for a US war hero, but a poet, who … while a war hero… was a FRENCH war hero.

Mexfiles has written before about Alan Seeger, whose poetic style and idealization of war might have, like other poet-soliders of the era, have gone on to a more developed, “mature” style, had his short life not ended with a unromantic, hardly ideal, gutshot in the trenches of the Somme in 1916. “He needed more time to move from a stock and outmoded romanticism to a more distinctive and original style, from a style full of abstractions to one more concrete and personal., as James Hart in the Dictionary of Literary Biography opined.

Seeger was only 28 when he died and had only lived in Mexico City for a few years when he was in his teens. But, considering Mexico was better known for as a safe space for those evading military service in the trenches of Europe, and — while his service was with the French Foreign Legion — he’s probably as close to a US World War I veteran with a Mexican connection you’ll find.

And… his time in Mexico City was not all that long… a few years as a young teen in the twilight of the Porfiriate. His father, Charles Seeger, Sr. is somewhat typical of the “expat community” of the era… a wealthy businessman looking for opportunities to exploit south of the border. What makes Charles Sr. an interesting figure is that what he found to exploit was not minerals, or agricultural products, or even lucrative railroad contracts… not directly, anyway. Seeger was one of the first to hit on the idea of business investment reporting… his bilingual Mexican Financier being a must read for both Mexican and foreign investors and wannabe investors. Perhaps it was dad’s success as a working writer that inspired both Alan, and his younger brother Charles, Jr. to taking up the pen, and publishing from time to time.

Although Mexican Financier ran into management problems in the late 1880s, it was profitable enough to sell, and return a very comfortable return that allowed the Seegers to live more than comfortably, bring the boys back from boarding school in the United States until they were ready for college, and for Charles Sr. to invest in other opportunities.

One of those opportunities… and a somewhat surprising one… was the new and exciting automobile. And not any automobiles: EVs! Yes, in the 1890s and up until 1910, it was a very lucrative business. The Electric Car Company (so much for snazzy corporate names). While somewhat more expensive than gasoline powered autos, they were hugely sucessful in cities (already electrified by this time), and the fleet cars they produced (which ran at a speed of 27 miles per hour or 40 Km per hour) were twice the speed of a trotting horse. They captured the New York City taxi market, and US cities were eager to acquire electric vehicles for their police departments.

The Seegers of Mexico City were… while not the 1% of the era… certainly seen as a brood of outside the box thinkers, with the money to spend on untried and new ideas.

Alan, enrolled at Harvard (as one would expect) turned to poetry, working with fellow student T.S. Eliot at the college’s literary magazine. Tom — the more unconvential poet — would opt for a conventional life, whereas Alan — the conventional poet — went in quite the opposite direction. As you might expect, upon graduation, Alan turned down a job with the Electric Car Company, and headed for… you guessed it, Greenwich Village. Where, of course, he ended up crashing with John Reed… whether Alan’s Mexican connections were a factor in Reed’s own interest in Revolutionary Mexico is debatable, though I’m not the one to start that debate. Both seem to have been in love with danger, and almost welcomed violence, although Reed focused on a romanticized proletarian future, while Alan seems to have internalized a sense of the romance of the past.

And where else to live in the romantic version of the past in the early 20th century than Paris. Despite the squalor of his digs in Paris (to which he complained in letters to his friends and family), the idealized “gloire” of the days of knighthood and an homorable death seemed to call him. With the outbreak of the First World War, he joined the French Foreign Legion, wrote his poems (and letters much less idealized, detailing the mud and slaughter of trench warfare). And earning a posthumous Croix de Guerre after his death on the fourth of July 1916. And even a statue (Place de Estas-Unis) in Paris.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Louis_Seeger_Sr.

While Alan’s posthumous poetry’s publication was largely financed by the family (which also would endow a library in Paris), the most immediate effect was on his younger brother, Charles, Jr. Charles, who had taken a more artistic route to writing than their father, was already becoming a well known music critic and professor.. However, he lost his job over his militantly pacifist objections to the US entry into World War I. Never giving up his pacificism and “internationalism”, Charles Jr. became a scholar of folk music, organized the collection of American folklore and music for the New Deal’s “WPA” and fathered a few radicals and outside the box children of his own, including the singer, songwriter, and peace activist Pete Seeger.

Other than Alan’s name on that building in Hipodromo, there isn’t all that much visible reminder of the Seegers… although with EVs more and more appearing on our streets (including taxis and police vehicles), foreign poets and “boheminans” aplenty, and a committment to peace and neutrality even at the highest levels of government in Mexico… the Seegers may be forgotten but a reminder that our ghosts — even expat ghosts — are reluctant to completely disappear.